Menu

50 Years On: Remembering the ‘Elton John’ Album, Part 2

To mark the 50th anniversary of Elton’s self-titled second album, we’re looking back on the record that made Elton a star.

This article is the second instalment of a three-part series. If you haven’t read Part One yet, which looks at the background and leadup to the recording of the album, you can do so here.

Part Two takes us back to the week of January 19, 1970, when the recording session began.

By John F. Higgins

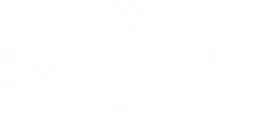

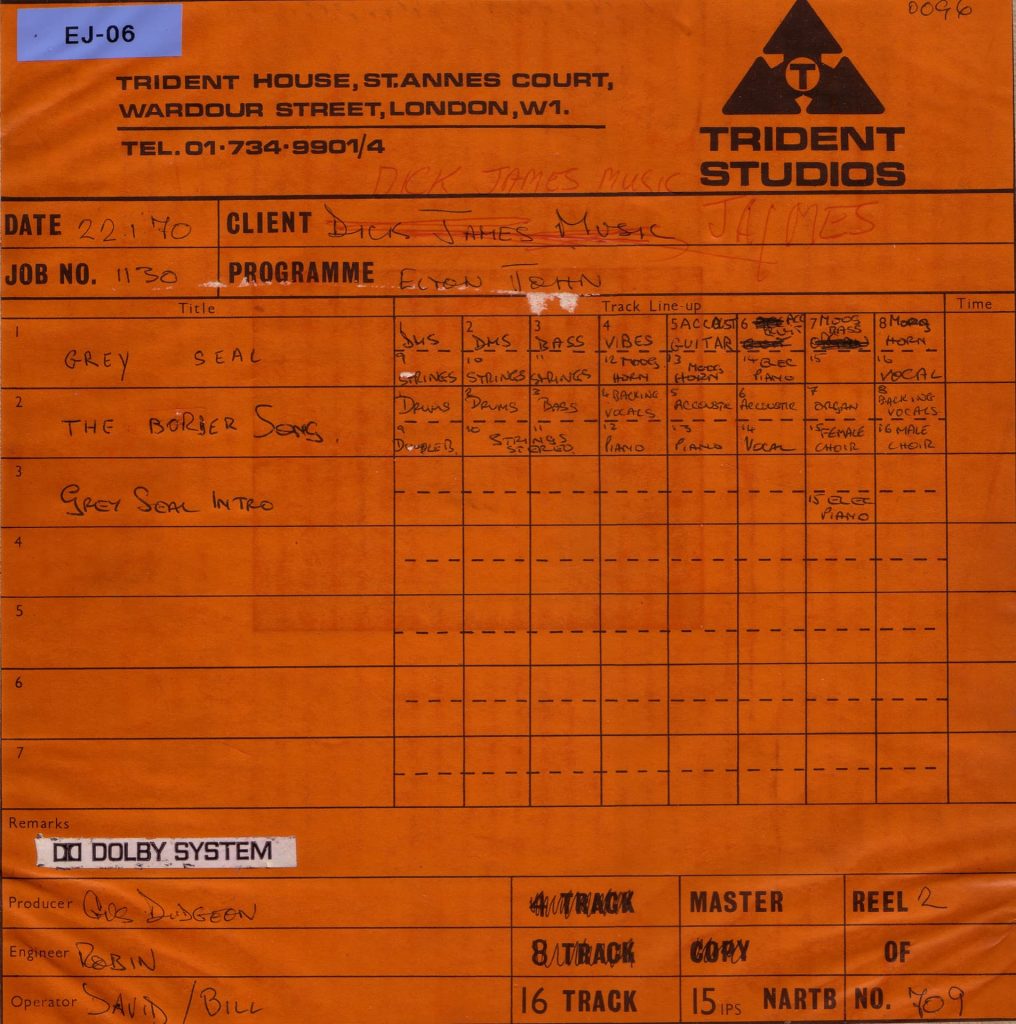

The recording of the Elton John album during the week of January 19, 1970 was broken down into two three-hour sessions per day: 3-6 pm and, following a dinner break, 9-11 pm (producer Gus Dudgeon has also referred to morning sessions, but that is not borne out by the master track sheets). This was standard per Musicians Union rules, which were very strict. If the session ran even a minute over, each musician would be paid double and the client, in this case, Dick James, would be quite reluctant to spend that sort of extra money, especially with an orchestra involved. Elton’s final vocals were done at the end of each day, with backing vocals for the songs that had them and some orchestral overdubs all being done at the end of the week.

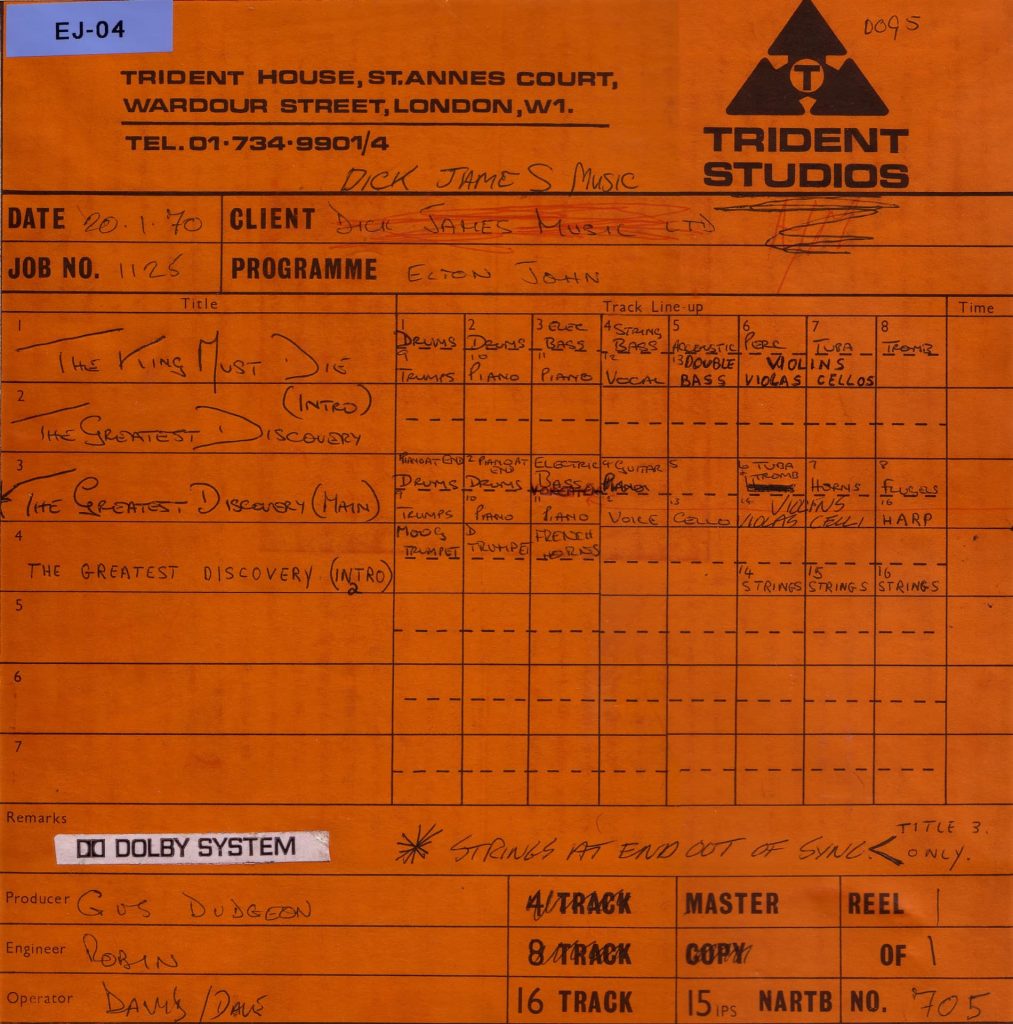

“The piano always went down with the first elements, that is, with the rhythm section (if there was one),” arranger Paul Buckmaster explained. “Everything else would be added to that. In some cases, we might record brass and woodwind together with the rhythm section and then overdub the strings. Actually, we did the strings live on I Need You to Turn To and, I think, The King Must Die. (That is one of my favourite Elton songs I’ve worked on because of the mysterious lyric and the humorous quality of the track.) Elton was screened off and the rhythm section was boothed-off from the rest of the musicians in the studio, which would have been a string section or brass section. Or woodwinds.”

We did all the tracks live, with strings… I was very, very frightened in the recording studio being confronted with a 40-piece string section and having to do it live. So that was quite nerve-wracking but it was good experience. When we all finished it, we were knocked out.

As producer Gus Dudgeon recalled in the 1990s, “The vibe for that week was on completely another level! We just never stopped smirking. We smirked 24 hours a day. All day long. We just kept going, ‘This is amazing.’ None of us had quite realised how amazing the whole thing was until it actually came out the speakers. The idea of taking a rhythm section and an orchestra and doing them live at the same time, with the kind of classical overtones within Elton’s piano playing and the way Paul Buckmaster wrote his arrangements on that album, added up to something completely unique. It was one of the most unique albums ever made in the history of pop. There’s no question about it. I can look from the outside and know that. The big thrill, which is silly really, was when you walked up Carnaby Street [a popular shopping area near Trident Studios] you heard that album coming out of every single boutique. It was either that or [The Who’s] Tommy.”

Guitarist Caleb Quaye also reflected on the musical environment. “We were all listening to the same music. We spent all our money on records at Musicland [the Soho record store where Elton would also work when he had the time] – we were influenced by a lot of “West Coast Sound” bands back in those days: Crosby, Stills & Nash, Jefferson Airplane, Spirit – and would listen and develop ideas and then just pour it out into the songs. Laura Nyro was a big influence on Elton, and also Joni Mitchell. He breathed all of that in. There were other things as well: Memphis – we loved Stax Records, Booker T. And The MGs. And obviously, Detroit (Motown). And we used to play little games at Reg’s flat in Pinner; we’d put on a record and then say, ‘Okay, where was it recorded? Who’s playing on it? Who produced it? Who engineered it?’ We got really good at that stuff. So in the studio, working things out, we’d say, ‘Oh, let’s put a bit of this in! Let’s have a Memphis start…’ or whatever. It was a great journey”.

“They spent an awful lot of money on equipment [at the studio],” Elton’s then-manager Ray Williams remembered. “The Sheffield brothers [owners of Trident Studios]. It was a huge leap from the Dick James studios! Everybody involved was just so enthused with everything and made great contributions.”

Artist David Larkham confesses, “I used to sneak over there during the sessions occasionally. I was supposed to be working on graphic design stuff [at the Dick James building, a five-minute walk from the studio on St. Anne’s Court] but knowing that everyone was over at Trident, I felt, ‘I’ve got to be over there – see what’s happening!’ It was an interesting education for me. I don’t know if I was being hoodwinked, technologically, by Gus, but there was one bit where he would have the orchestra finish a take and he’d say, ‘That was good, guys… but I’d like you to do it again.’ And then he and Robin [Geoffrey Cable, engineer] would talk together, and Gus would say, ‘That was actually perfect, but if I get them to do it again and add it on top, it will sound like the orchestra is twice as big!’ I don’t know if he was making that up for me or if he was actually doing that sort of thing.”

TRACK-BY-TRACK

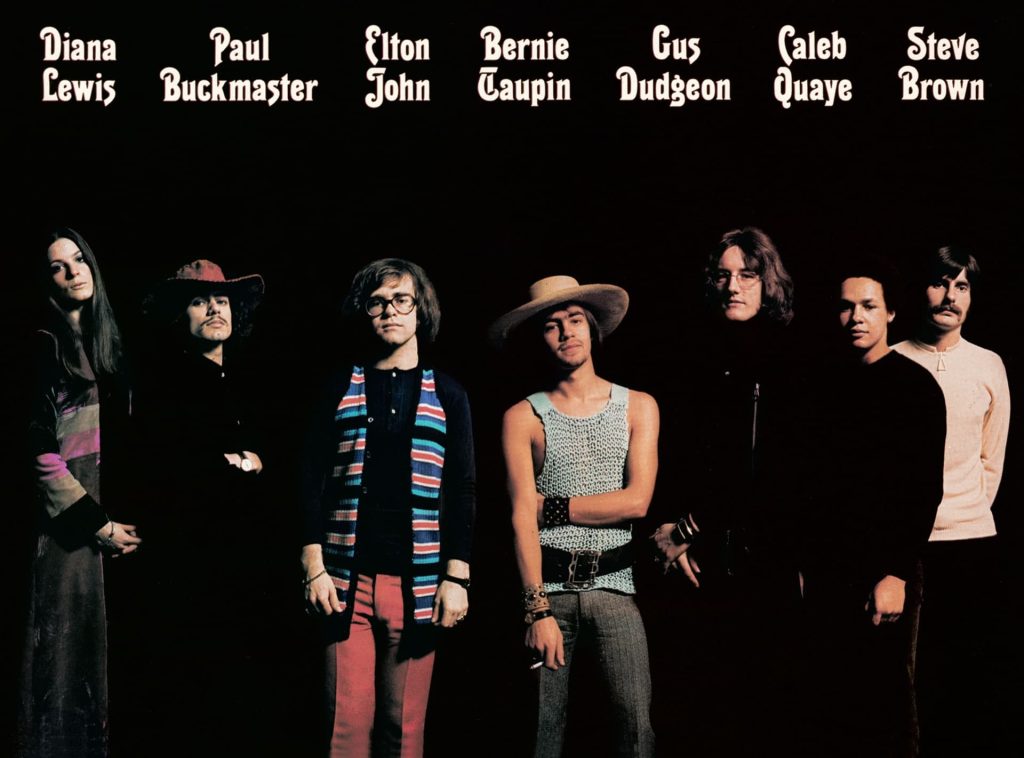

Your Song

Written: October 27, 1969

Recorded: January 22, 1970 (3-6 pm session) – Take 3 of 3.

Musicians

Elton: piano and vocals / Clive Hicks: 12 string guitar / Colin Green: acoustic guitar / Barry Morgan: drums / Frank Clark: acoustic guitar / Dave Richmond: electric bass / Herbie Flowers: string bass? – uncredited / Skaila Kanga: harp – uncredited / orchestra.

When asked by radio presenter Paul Gambaccini in 1976 about the line “Anyway, the thing is, what I really mean… “ Elton said, “With lyrics like [Bernie] writes, I’m an expert at fitting a lot of words into one line. It’s a matter of phrasing your voice. And throughout the years I’ve gotten better and better at it.”

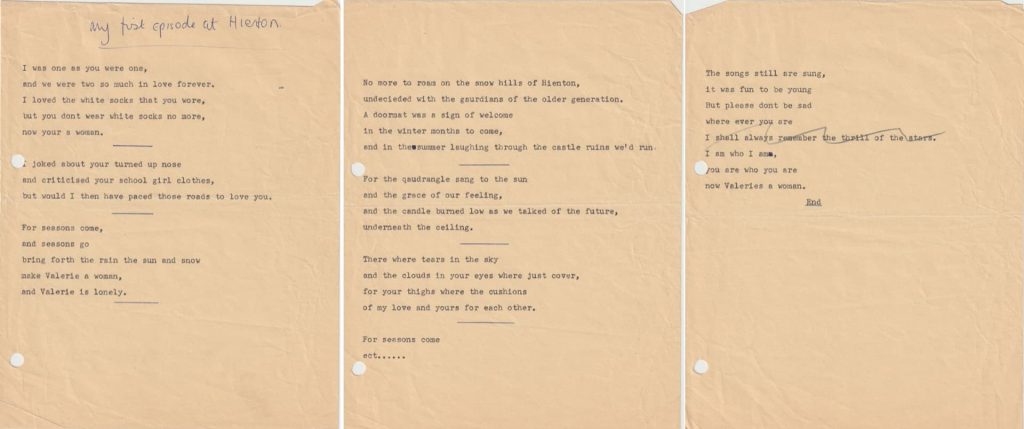

Bernie further explained, “I wrote the song after having bacon and eggs at [Elton’s] mother’s flat in Pinner, while he was having a bath in the other room. And I wrote it on a piece of mathematic exercise paper.” Speaking to Elton’s statement that the lyric was about Bernie’s girlfriend at the time, “It was written for everybody in general and not anybody in particular.” Apparently, First Episode At Hienton is about a specific person, named Valerie, but not Your Song.

I Need You To Turn To

Recorded: January 21, 1970 (9-11 pm session).

Musicians

Elton: electric harpsichord and vocals / Roland Harker: guitar / Skaila Kanga: harp / orchestra.

The demo to this song was a piano/vocal. Somewhere along the line, it was decided to record it on harpsichord, as Skyline Pigeon had been tracked on the Empty Sky album the year before. (Both songs, by sheer coincidence, had the harpsichord in the left channel and Elton’s vocals in the right.) Gus tells, “We’d discussed the fact that being as the album was to be more orchestral than anybody else had attempted to do, why not use other keyboard instruments? It’s nice to break away from that one consistent piano sound sometimes.” Upon listening to the song in the 1990s, Gus determined that a mono electric harpsichord was used. “I imagine I’d probably have him tucked away in the drum room, away from the strings, for separation’s sake. We’d have a talk-back mic, so if he wanted to say something, we could hear him. Especially with the electric harpsichord not being mic’d. And occasionally he would lean into that mic and sing the odd word here or there, as a guide…to himself more than anything else.”

Take Me To The Pilot

Recorded: January 22, 1970 (7-10 pm session? 8-track).

Musicians

Elton: piano and vocals / Caleb Quaye: electric lead guitar (1964 Fender Stratocaster) / Alan Parker: acoustic rhythm guitar / Barry Morgan: drums / Alan Weighill: bass guitar / cellos. Overdubs: Madeline Bell, Tony Burrows, Roger Cook, Lesley Duncan, Kay Garner, Tony Hazzard: backing vocals / Dennis Lopez: percussion-congas.

Caleb notes that “This was the only solo I did on the album. Paul had that written out. This was the first time they’d done a lead solo part with the strings. We did the basic track. Then they put the strings on (I was there for the string overdubs [just a section of 12 cellos]). Then Paul said, ‘I would like you to double the strings.’ It was his idea; he’d written that out… nobody had done that before.”

Astute listeners will notice two different piano parts in this song: one during the overall track, which is in the left channel, and then, in the right channel, an overdub for the piano break between verses. Gus explains: “He had trouble playing that little lick. Keeping it in time. So, we dropped [a piano overdub] in, with the drummer keeping time [off-mic]. And he comes back in on the left-side speaker with that big chord [to go to the next part in the song].”

No Shoestrings On Louise

Recorded: January 19, 1970 (8-track).

Musicians

Elton: piano and vocals / Caleb Quaye: electric lead guitar / Clive Hicks: acoustic rhythm guitar / Barry Morgan: drums / Alan Weighill: bass guitar. Overdubs: Madeline Bell, Tony Burrows, Roger Cook, Lesley Duncan, Kay Garner, Tony Hazzard: backing vocals / Dennis Lopez: percussion-congas.

A favourite of both Bernie Taupin (“It’s so out of context on that album; it could have been on Tumbleweed”) and Gus (“I always sing along with this track. Without fail. When he goes ‘There ain’t NO…’ I’m In!”). The lead vocal is an intentional nod to another popular singer – “You can hear the Jagger influence in the vocal…’Caddilayak’!”, Gus notes. He continues, “The piano is on the left, simply providing more of a rhythm part and giving space for the big, chunky acoustic guitar on the right. Great drummer on this (and most of the album), Barry Morgan. I remember him coming up to me and thanking me. Shaking my hand, I mean, really pumping my hand and saying, ‘I’m just so pleased you asked me to come and do this album. I just love this guy’s stuff.’”

First Episode At Hienton

(Lyric written as “My First Episode At Hienton”)

Recorded: January 21, 1970 (9-11 pm session).

Musicians

Elton: piano and vocals / Caleb Quaye: lead guitar (1964 Gibson J-45) / Skaila Kanga: harp – uncredited / orchestra. Overdubs: Diana Lewis: Moog Modular synthesizer.

Caleb: “I tracked that live in the studio with Elton. That was part of our musical chemistry since we first started playing together. It wasn’t like ‘work’. It was fun. I’d sit down and watch him play and figure out where he was going”.

The Moog synthesizer part holds a special place in the hearts of this song’s fans. “That wasn’t an instrument that we knew very much about,” Gus explains. “Even when we finished using it, we still didn’t really know what it was doing. It was bigger than all of us. And that was Paul’s idea, to use that. Diana [Lewis] was his girlfriend at the time – soon to be his wife.” The Moog Modular was rented from George Martin’s AIR Studios and, according to Paul, the part was done when he was out having lunch one day. “It consisted of four boxes about the size of medium suitcases and a 61-note keyboard. Only one note at a time could be played. The keyboard had a ribbon across the top, which Diana played with her left hand, to create those wonderful glissandi and the natural vibrato. Diana helped lift this beautiful song to heights none of us imagined. The excellent (totally analogue) reverb was applied, live, right there during Diana’s one take, by engineer Robin Cable.”

Sixty Years On

Recorded: January 22, 1970 (3-6 pm session) – Multiple takes. Intro recorded separately.

Musicians

Elton: vocals / Colin Green: Spanish guitar / Brian Dee: organ / Skaila Kanga: harp – uncredited / orchestra.

The György Ligeti-inspired beginning of Sixty Years On, which Paul was often complimented on through the years, was in fact recorded separately from any song and stuck on by Gus. “There was some downtime in the studio during a string session,” Paul recounts. “So, just for fun, I dictated a set of notes to the string section, which they wrote down. Very simple – maybe one or two notes to each group of three or four players. We had 21 strings on that date. I proceeded to conduct them after having told Robin Cable to start recording. This was off the top of my head; there was nothing planned about this. The first entry was, say, a viola note. Two of the violas started with the first note. And as I wasn’t conducting to a beat, I would then point to the next two violas that came in with the next note. Then two of the second violins would come in with the next note. And so on until the whole section had joined in. I had also indicated where I wanted certain kinds of vibrato (wide or narrow), which helped to create that effect. So, we recorded that… and there it lay. And Gus went on to add that to the front of Sixty Years On [the producer edited the piece down by 20 seconds for the final album]. I hadn’t conceived the arrangement that way.”

Border Song

(Recorded as “The Border Song”)

Recorded: January 22, 1970 (7-10 pm session)

Musicians

Elton: piano and vocals / Clive Hicks: acoustic guitar / Colin Green: acoustic guitar / Barry Morgan: drums / Dave Richmond: bass guitar / Brian Dee: organ. Overdubs: orchestra with double bass / Barbara Moore Singers: choir with Barbara Moore as choir leader) / Madeline Bell, Tony Burrows, Roger Cook, Lesley Duncan, Kay Garner, Tony Hazzard: backing vocals.

Elton explained to Paul Gambaccini how he came to write the lyrics for the third verse of this song (referencing Caleb Quaye in the last couple of lines), “It was only two verses long, originally. And I just plunked the other one in.” Bernie adds, “The sentiments in that song, in fact, didn’t mean anything. The great thing about Elton’s last verse was he tried to put it all into perspective. That song is probably two totally separate songs.” The duo also reflected what it meant to them to have one of their idols cover their composition: Bernie – “When Aretha Franklin covered it, I think that was our biggest buzz up to that date!”; Elton – “I was thrilled but then I was disappointed because Aretha, up to then, had had six or seven #1s in the States… and then she brought out Border Song as a single and I think it only reached 21 on the American charts. So, I really felt guilty.”

The Greatest Discovery

Recorded: January 20, 1970

Intro (Moog trumpet, D trumpet, French Horns, 3 tracks of strings) recorded separately during same session. Horn version released on Portugal LP only.

Musicians

Elton: piano and vocals / Clive Hicks: acoustic guitar / Terry Cox: drums / Dave Richmond: bass guitar. Overdubs: Skaila Kanga: harp / Paul Buckmaster: solo cello / orchestra.

In June 2018, a life celebration for Paul Buckmaster, who had died the previous November, was held at his preferred recording studio: Capitol Studio B in Los Angeles. Unable to attend, Elton requested that the first song played be The Greatest Discovery, as it was his favourite arrangement of Paul’s, in no small part because of the fact that Paul himself played on it.

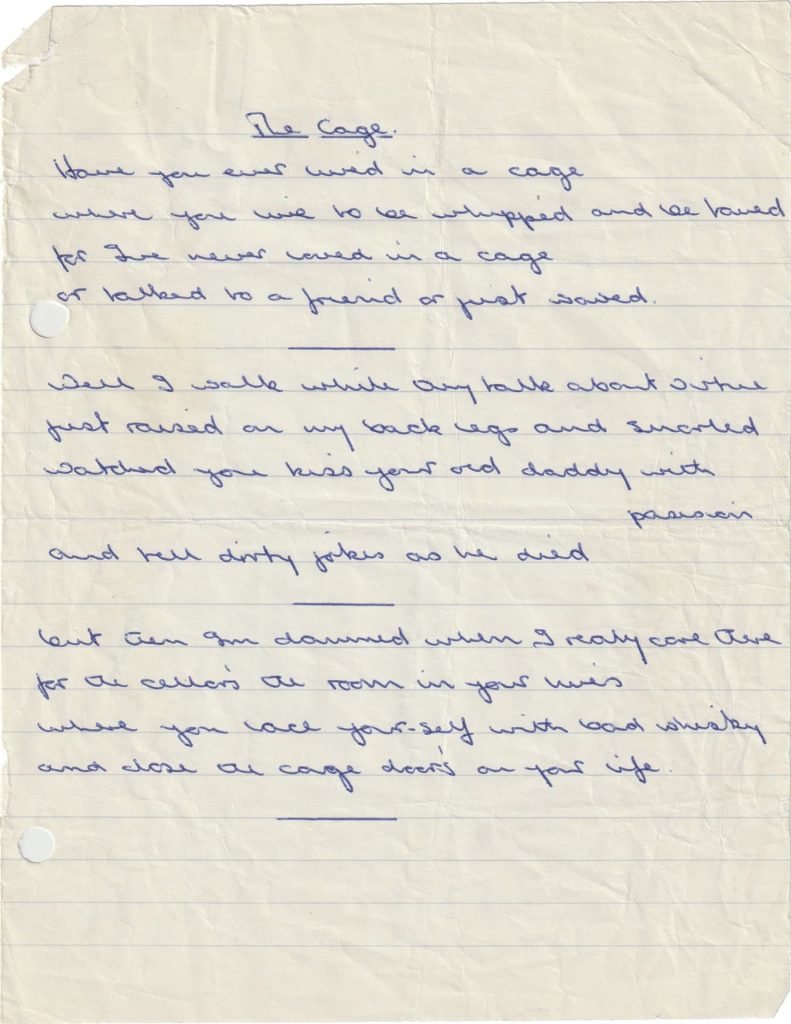

The Cage

Recorded: January 20 or 21, 1970.

Musicians

Elton: piano and vocals / Caleb Quaye: electric guitar / Clive Hicks: acoustic guitar / Barry Morgan: drums / Alan Weighill: bass guitar. Overdubs: Diana Lewis: Moog Modular synthesizer / Madeline Bell, Tony Burrows, Roger Cook, Lesley Duncan, Kay Garner, Tony Hazzard: backing vocals / Tex Navarra: percussion-congas, shaker / horns.

Having been demo’d at Dick James Music on October 28, 1969, Bernie’s darkest lyric on the album is given the full-bore treatment at Trident… with no orchestration but plenty of horns in the arrangement. The solo on the song sounds like horns as well, and was originally written by Paul Buckmaster for brass, but is Diana Lewis once again playing the monophonic Moog synth.

Original lyric sheet for 'The Cage'

The King Must Die

(Lyric written as “And The King Must Die”)

Recorded: January 20, 1970

Musicians

Elton: piano and vocals / Clive Hicks: acoustic guitar / Terry Cox: drums / Frank Clark: acoustic bass / Les Hurdle: electric bass. Overdubs: Dennis Lopez: percussion / orchestra with trumpets, tuba, trombone.

Inspired, lyrically, by a book of the same name by British author Mary Renault, the song was demo’d at Dick James Studios on October 1, 1969 with just Elton on piano and vocals. This is one of Paul Buckmaster’s favourite Elton songs: “It got my goose-bumps”. On the Trident recording date, Elton was screened off, and the rhythm section was boothed off, from the orchestra…as was the case on many of the other session. Two stanzas from Bernie’s original lyrics were removed during Elton’s writing of the music, an occurrence that was not unusual in their partnership.

We will go into detail on the bonus tracks from the Elton John album, and its impact upon release, in Part 3 of “50 Years On: Remembering the ‘Elton John’ Album”, for Record Store Day.

Interviews with Gus Dudgeon and Paul Buckmaster: 1993-1996

Interviews with Skaila Kanga, David Larkham, Caleb Quaye, and Ray Williams: March 2020

Select quotes from Paul Gambaccini radio special, ‘The Elton John Story: Keyboard Wizard’ (July 1976)

EltonJohn.com thanks David Bodoh, Keith Hayward, John McEwen, and Peter Thomas for their research assistance.