Menu

50 Years On: Remembering the ‘Elton John’ Album – Part 1

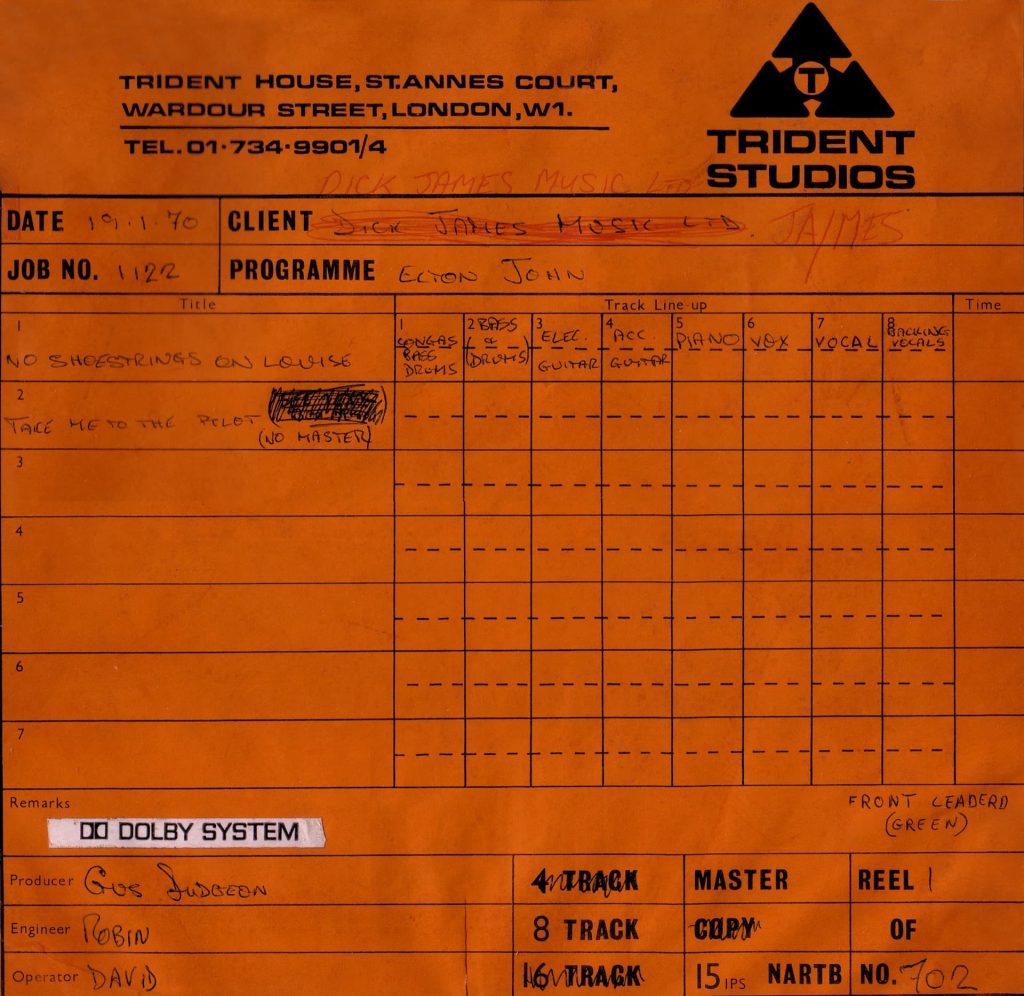

While it may not have been his first full-length release, Elton John’s self-titled second album was the one that made him a star.

Released fifty years ago today by DJM Records, on April 10, 1970, Elton John was Elton’s second album. In the United States, where it was released on Uni Records later in the year, many assumed it was his debut record as Empty Sky was not given an official release until 1975.

This year, we’re celebrating the 50th anniversary of an album that launched a young British singer-songwriter onto the world stage with a three-part series on EltonJohn.com, exploring the history of the album, and a limited-edition Record Store Day exclusive deluxe gatefold 2LP.

This article, Part 1, explores the background and lead-up to the recording of the album. Stay tuned for Parts 2 and 3 to follow.

By John F. Higgins

The album which I am quite proud of is the very first one [I did with Elton]. The 'black album' was all done in a week. If I could go through that week again, I would just love it to death.

After the release of Elton John’s first album, ‘Empty Sky’, in June 1969, it came time to consider the follow-up.

Elton and his lyricist, Bernie Taupin, had already written a number of songs that had not been included on the debut and the duo were showing no signs of slowing down their creative output. In fact, Elton had already performed one of the songs that would later appear on the Elton John album, First Episode At Hienton, on BBC Radio (John Peel’s Night Ride) as early as November 27, 1968.

Perhaps more to the point, Empty Sky had declined to take the British listening public by storm, so new product had to come forth or else Elton’s recording career could possibly end as soon as it had begun. It wasn’t a question of the material’s quality, everyone in the inner circle of Dick James Music agreed that the new songs continued to show exponential growth, but more how best to present the music. Empty Sky’s producer, Steve Brown, who was Elton and Bernie’s primary creative advocate within the company, ran through a few of the latest tracks, including Take Me To The Pilot, The Cage, Rock And Roll Madonna, and Border Song, with Elton and his “live band”, Hookfoot (with future Elton band members Caleb Quaye and drummer Roger Pope), at Olympic Studios in London in August and September 1969, most likely to see how the next album might come together.

There was so much output of music. They loved writing the songs. They couldn’t wait to get in the studio to do the demos!

As Caleb recalls, “Steve was a great champion of us writing and pursuing the music that we felt. Not only were we a [music] team, we were friends. We were mates. We all hung out together. For example, David [Larkham] wasn’t just some art contractor hired to design the album cover. He was there… he was a part of it all. There was a lot of relational chemistry involved. We were all in on it.”

David agrees, “I remember we’d all go from Dick James’ building over to Musicland, the record store in Soho, buying up American imports, listening to them in the evenings, often over at Steve’s flat. It’s all part and parcel of being music fans, as well as music creators within the music industry. All part of the fun of it. You could tell when Bernie had heard The Band, because that was when all the Tumbleweed Connection lyrics started coming out.” Remarkably, by the time the Elton John album sessions began, most of the songs for its follow-up had already been written.

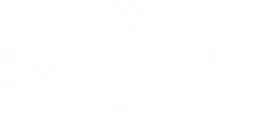

The back cover of 'Elton John', featuring those who created it.

During the fall of 1969, Elton continued to demo the aforementioned “black album” songs, as well as The King Must Die, No Shoestrings On Louise, and I Need You To Turn To at Dick James Studios on New Oxford Street while meetings were held on next steps. Your Song was written on October 27 and demoed soon after, so now eight of the album’s eventual ten titles were under development.

Elton’s then-manager, Ray Williams, remembers how Your Song stood out. “I mean, I couldn’t help thinking, ‘How could somebody so young [19] write the lyrics for that?’ It was just so amazing”. David concurs, “We all wondered that.”

The song so impressed Steve Brown (“I just went wild straight away…I thought it was incredible!”) that he suggested to Elton that it be his final production for the pianist, as a one-off single. This meant a search had to be done to find an arranger worthy of the material.

David Bowie’s Space Oddity peaked at #5 on the UK charts on November 1. The following day, Steve and Elton met with its bold arranger, Paul Buckmaster at a Miles Davis concert at Ronnie Scott’s in London. Soon after, Paul was given the demo of Your Song and responded with fervor.

It only took the first hearing for me to call Steve and express my enthusiasm. I heard the potential of what l was going to write. I had already begun to hear what I was going to write on ‘Your Song’, for a start. It was the sort of thing that I was dying to have a go at.

Steve then played Paul the rest of the demos, in the hopes of selecting one of them for the proposed single’s b-side, and the arranger was so knocked out by each successive song that he finally told Steve that he was no longer interested in just doing a one-off…he wanted to arrange an entire album of Elton’s material.

Following some reflection, Steve made the generous and difficult decision to step aside as producer. “I just realized that I hadn’t got the experience and the expertise to produce an album that was going to involve a 50-piece orchestra and 16-track recording,” he explained on Paul Gambaccini’s Elton John Story BBC radio programme in 1976. “All that I had ever done before was with three or four musicians on a four-track studio.”

David Larkham notes that, “Empty Sky was quite an exciting project for us all. But after that, people like Steve said, ‘This is good, but it’s got to get serious now. It’s got to get better.’”

Steve and Elton asked Buckmaster who he would suggest produce the album. Immediately, the name of Gus Dudgeon, who had helmed Space Oddity and other one-off hits, was put forward. He, too, met with Elton and Bernie…and it did not start well. Gus later said, “Actually, for the first half-hour of the meeting, I thought Bernie was Elton because Steve never introduces anybody to anybody; he just walks in and expects people to know who the hell they are. Bernie was kind of younger, thinner and didn’t wear glasses and had longer hair. I thought [laughing], ‘He must be the artist!’ Mind you, Elton was dressed like a traffic light, which I guess should have been a bit of a clue.”

Gus was played the demos and his reaction was varied, depending on who is telling the story. Elton and Steve felt that Gus was so-so at first and had to be given some time to come on board. Gus recalls it differently: “I was absolutely thrilled with [the songs]. I apparently didn’t look this way. I’m always told by Steve and Elton that I looked really quite uninterested. I’ve heard this, but I don’t remember doing that. Maybe I did it on purpose. I was trying to look cool or something. But [inside] I was leaping up and down thinking, ‘Wow!’”

“I called up Steve and he said, ‘How much advance do you want?’ I said, ‘2,500 quid.’ And he said, ‘What?? Dick’s never paid that much advance in his life on an album. You might be lucky if you get a thousand.’ I said, ‘Steve, come on, it’s not that much money. That’s what I want.’ And he said, ‘Gus, you may lose the gig.’ I said, ‘That’s the risk I’m prepared to take.’ So then he said, ‘What sort of budget have you got in mind?’ And I said, ‘Well…carte blanche?’ And he went [exasperated], ‘Now, Gus, you’ve got to give way on one of these because I know Dick and he ain’t going to agree to these.’ So I said, ‘Well, it’s got to be that way. Until I get into this in major detail, I don’t know how many strings I need and how many musicians and for how long and blah-blah-blah.’ Anyway, eventually I went to Dick with a budget and I said, ‘Dick, really I need carte blanche. I need to know that if I want some more money, I can come for it.’ And he said, ‘No problem.’ I never actually had to go back for more money; I had what I needed when I needed it. He just paid every bill and there was no further discussion. It cost £6,000 to make [about three times the budget for an established artist’s album at the time], including the sleeve, which is absolutely peanuts. I mean, some people can’t make a single nowadays for £6,000, myself included.”

Caleb offers, “Gus could do that because he’d had some hits. He had credibility.”

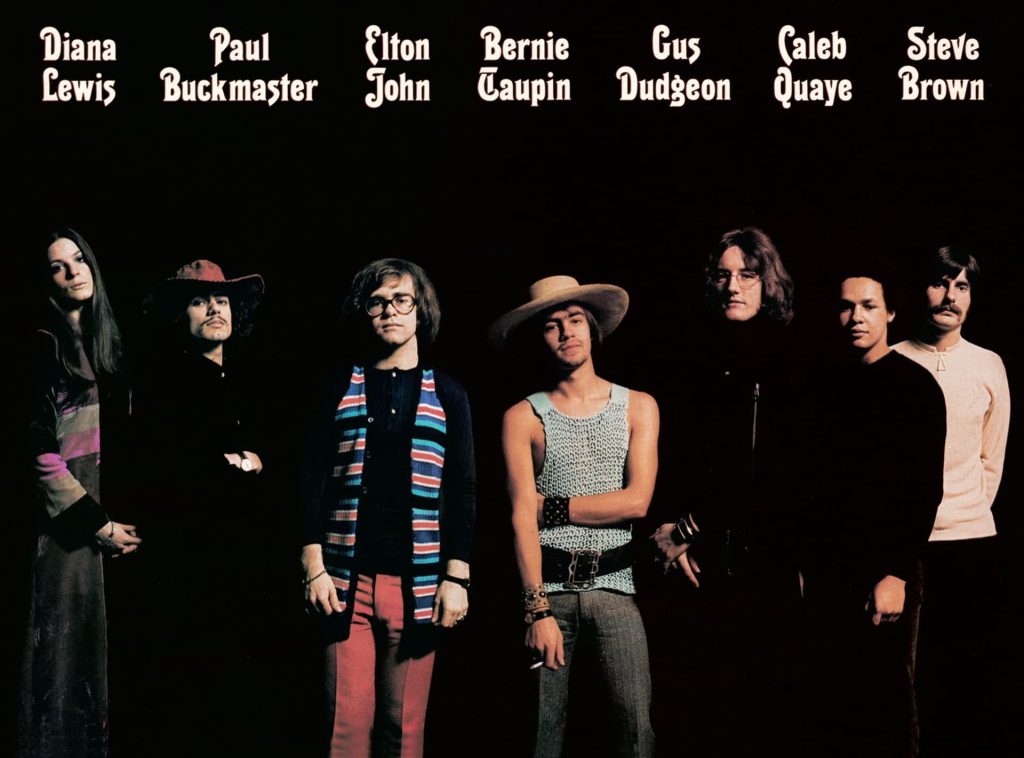

Scan of master tape box from first day of recording the 'Elton John' album.

A studio was selected: Trident, where Space Oddity had been recorded the year before and home to a 100-year-old Bechstein piano that was used on a multitude of ground-breaking hit songs, from The Beatles’ Hey Jude to, five years later, Queen’s Bohemian Rhapsody.

Ray Williams notes, “There was another very important thing about Trident – it was near the pub next door. ‘The Ship’, maybe? And you had the Marquee [nightclub] around the corner.” Caleb adds, “There was a great Indian place nearby, so we used to get curry delivered during the session breaks”. “It’s actually quite amazing that so much got done, with all those distractions,” concludes Ray!

Once all the creative pieces were in place, in late winter 1969, they all “decided to plan an incredible, orchestral album,” as Elton put it to BBC Radio in 1973. “The sort that had never been planned before. A really pop album with a lot of heavy orchestra in it but with a beat as well. You know, really sort of funky stuff.”

Gus and Paul, as they had done with the Bowie hit, went about the job of figuring out the entire album before anyone even set foot in the recording studio at 17 St. Anne’s Court in Soho. Elton pointed out that they, “Calculated that album, detail by detail. It took a lot of planning. Meetings five days a week. All the notes were written down, even the rhythm notes.”

According to Paul, “Gus and I would meet in his office and sit at his table, listen to the demos, follow the songs on the lyric sheet and make notes next to the relevant lines. We went through every song, possibly, in two sessions in his office. We would discuss where we would like the first string entry, if that was the case. Say it was a song where the piano started, for example, Your Song. We would say, ‘Okay, we will start with strings in the first verse. We won’t bring the drums in until the second verse.’ Stuff like that. After having done the “routining” (that’s what this process is called), I would take the notes home with me and start scoring and let my imagination have full rein.”

Gus adds, “They’d all be chucking in ideas as to what kind of thing we would want in a solo, for example. You know, throwing ideas around in my office.”

“As a matter of policy,” Paul continues, “Elton decided to not be involved in the creative decisions that Gus and I made. Elton literally said, ‘I don’t want to be involved in this. I trust you guys.’ He was wonderful. It’s not often that you have an artist do that. He had so much trust that he allowed us to do what we felt was right for each song. Each song was its own mini-film that had its own cast. We treated each song as an individual entity in itself.”

Caleb adds, “They were meticulous. And Paul Buckmaster was a genius! He was great to work with; he was kind of like our teacher in many ways. He upped everybody’s game. It was just a great team – great chemistry.”

During this process, calls were put out to some of the premier studio session musicians of the day. “People like Terry Cox, who’s with Pentangle,” Elton told Terry Towne for Jazz and Pop magazine in 1971. “And Barry Morgan, the other drummer, is with an English group called Blue Mink [the British band also included bassist Herbie Flowers, who recorded on this album, and future Elton percussionist Ray Cooper]. All the other people are really sort of the top session guys, the backup singers are all the best backup singers.”

One notable member of the orchestra was harpist Skaila Kanga, who had first met Elton when he was Reg Dwight at the Royal Academy of Music. As she recalls, “I knew Elton when we were 11 or 12 years old, because we were in the same harmony, counterpoint, oral and dictation classes at the Junior Royal Academy of Music on Saturday mornings. I remember him but he kept himself sort of under the radar. He was training as a classical pianist at that time and it was not in his comfort zone, so he kept himself a little bit hidden. But having said that, he knew what he wanted to do, and it wasn’t really down the line of classical music. He’s got a different sort of most fantastic memory; he can sit down and play an improvised song and remember every single note!

“Paul Buckmaster was also there in the Juniors at that time, as a cellist. Elton left when he was 15 and I and a load of others went on to do A levels at school and then joined as full-time students at the Academy, by which time Elton had gone on to do all sorts of other things in a different area. When I was 24 I was booked for these sessions at Trident, amongst many others I was doing at the time, and Paul Buckmaster came in and I said, ‘Oh, hi Paul! How are you?’ I remembered him. And he produced this huge bunch of music that was black-looking, basically. Absolutely looked like Rachmaninoff to me. It was a big ask to do this stuff, just sight-reading it, because it was all hand-copied.”

As state-of-the-art as Trident was at the time – it was one of the first UK studios to offer 16-track recording – there apparently were not enough headphones to go around for the orchestral players. “What we had was little, tiny speakers next to us, with a little bit of drums in, I think,” Skaila describes with a laugh. “So that’s why it’s all a bit loose! We couldn’t have the voice in the speakers, because it would [leak onto the finished track], so we had this sort of small type of rhythm track…and there we were, all playing along with these millions of notes to this little speaker on the floor!”

The Elton John album sessions began at Trident Studios on Monday morning, January 19, 1970, with Robin Geoffrey Cable engineering and future Elton engineer David Hentschel as one of the tape-operators. The first songs tackled, on eight-track, were No Shoestrings On Louise and an unsuccessful attempt at Take Me To The Pilot. As Gus explains, “We did some of the songs on eight-track and some of the songs on 16-track, to keep the budget down. The stuff with the really big orchestras was done [subsequently] on 16-track.”

We will give a song-by-song account of the album, with recording details, in Part 2 of “50 Years On: Remembering the ‘Elton John’ Album”, next month.

Interviews with Gus Dudgeon and Paul Buckmaster: 1993-1996

Interviews with Skaila Kanga, David Larkham, Caleb Quaye, and Ray Williams: March 2020

EltonJohn.com thanks David Bodoh, John McEwen, and Peter Thomas for their research assistance.